What to Wear in the Mexican Caribbean

There is something about a tropical climate that instantly lifts your mood – so dress to match your serotonin levels. Style expert Osman Ahmed leads us through the do’s and don’ts of a tropical holiday to the Caribbean coast of Mexico, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.

Read more - What to Wear in the Mexican CaribbeanHow 500 Brushstrokes Become One

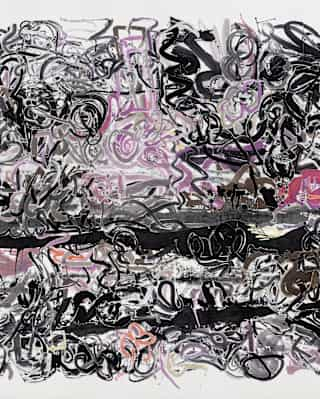

“Human encounters are truly magical.” In an era shaped by artificial intelligence and rapid technological change, this reflection by Chinese artist Wu Jian’an feels quietly radical. It also serves as the emotional core of 500 Brushstrokes in Peru, his ambitious travelogue and participatory art project, soon to be exhibited at Art SG Singapore.

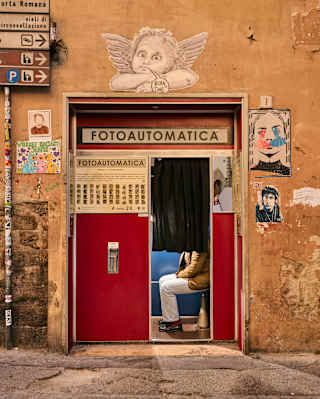

Read more - How 500 Brushstrokes Become OneThe Artisans Reimagining Florence’s Finest Hotel

Italy’s ultimate retreat and Renaissance haven, Villa San Michele occupies a privileged perch on the hills overlooking Florence. Set within the original monastery and gardens, every space is designed to deepen the connection to Florence’s breathtaking landscape and rich culture. Discover the artisans reviving this Renaissance legend, reopening in Spring 2026 after a complete renovation.

Read more - The Artisans Reimagining Florence’s Finest Hotel Recipe: Esquites with Marrow

A touch of decadence in a single-serving cup, these esquites with bone marrow are a reminder that Mexican street food doesn’t always need to be minimal or pure – it can also be fun, a little wild and exactly what you want when the day gets too serious.

Read more - Recipe: Esquites with MarrowBelmond’s 2026 Culture Calendar

With our properties situated across some of the world’s most culturally rich destinations, our 2026 calendar highlights must-see music festivals, art fairs and luxury travel experiences around the globe.

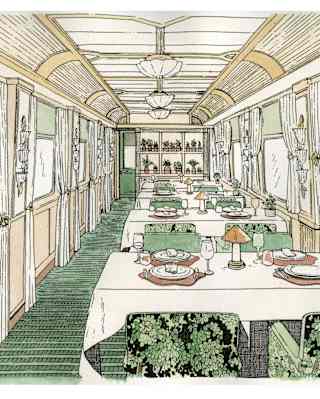

Read more - Belmond’s 2026 Culture CalendarWhat to Wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express

It’s the one place in the world where it’s impossible to be overdressed. Style expert Osman Ahmed reveals her top tips on what to wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express train, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.

Read more - What to Wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express Where Nature Blossoms into Art

Discover how artist Anna Deller-Yee reinterprets Belmond’s iconic gardens – from bergamot to jasmine – in a limited-edition festive candle and trinket tray celebrating global biodiversity.

Read more - Where Nature Blossoms into ArtHello From the World’s Highest Beach

Most beaches meet the sea, however, this one greets the sky. Stake your spot at Collata Beach on Lake Titicaca’s Taquile Island, where Belmond’s Andean Explorer is offering a rare trip to the shore at an altitude of nearly 4,000 metres.

Read more - Hello From the World’s Highest BeachAnd The Winner Is…

The Belmond Photographic Residency, now in its second year, has crowned a new winner. Meet Tara L. C. Sood and her award-winning submission.

Read more - And The Winner Is…