Play The Sun Before Dawn

Play The Sun Before Dawn

Join photographer Nick Ballón on a photographic journey through the vibrancy of modern Peru, while tracing a complex family history deep into the ancient Incan Empire.

In April 2024, Ballón and the writer Laurence Blair set out on the trail of Mansio Serra de Leguizamón – often called the Last Conquistador. As well as playing a formative role in one of Peru’s most painful periods of history, Serra de Leguizamón happens to be a distant relative of Ballón’s. Dying in 1589 in Cusco – the former Inca capital – aged 78, Serra de Leguizamón was allegedly wracked with guilt at his part in destroying the Inca realm, which by then then he saw as a lost utopia where “all things, from the greatest to the smallest, had their place and order.”

Following Serra de Leguizamó’s trail, Ballón used Belmond’s hotels in Cusco and the Sacred Valley as a springboard to trace the conquistador’s six-decade career of greed and repentance. Far from a homage to his distant relative, Ballón’s images focus on the resilience, creativity and ingenuity of Andean communities as they strive to keep their identity alive amid a rapidly changing society.

Image above: Shadows fall on the Nazarenas Suite at Palacio Nazarenas, A Belmond Hotel, Cusco, probably Mansio’s former bedchamber.

Tawantinsuyu, the Inca Empire, stretched for 2,500 miles between Colombia and Chile: the length of London to Timbuktu. It also spanned huge vertical distances, with terraces and irrigation channels winding down Andean slopes some five thousand metres high.

On the mountain opposite Ollantaytambo, the Inca site of Pinkuylluna glows in the morning sun. The ruins are thought to have been granaries, storing the plentiful produce grown in the Sacred Valley

Though worship of the Inca Sun God, Inti, was officially outlawed by the Spanish, the surviving Inca nobility incorporated solar imagery into their portraits and coats of arms.

Since being popularised by Hiram Bingham III in the mid-twentieth century, Machu Picchu remains the most iconic symbol of pre-Columbian Peru. But the soaring Inca citadel is barely 600 years old: a mere stripling compared to earlier Andean civilisations.

A garage door in Urubamba, a bustling commercial hub in the middle of the Sacred Valley, is designed to look like Inca stonework.

In the wake of an 1780 uprising lead by Tupac Amaru II, a descendant of the Incas, Spanish officials forbade Andeans wearing traditional dress. But the imposed European fashions of the age – bowler hats, knitted petticoats and flowing skirts – have since been reclaimed as a marker of identity in Indigenous communities across the Andes.

Locals walk past imitation Inca stonework made of pebbledash in Urubamba.

Stems of abatia parviflora, known locally as duraznillo and used to make black dye, wave in the Sacred Valley. Though native to the Americas, the tree is named after a colonial-era plant scientist from Seville, Pedro Abad y Mestre. The Spanish empire in the Andes not only extracted silver and labour but also foodstuffs and botanical knowledge.

A doorway at Vitcos, the capital of Manco Inca – a rebel emperor who escaped colonial Cuzco. He founded a dynasty that held out in the mountains of the Vilcabamba for a generation.

A mossy mandor tree lours over the hillside at Mandorccasa. A kind of carob, mandors can live for hundreds of years. This one may have witnessed Mansio and his fellow conquistadors marching down to capture Manco’s sons at Espíritu Pampa.

Edgar Roman pulls aside a curtain in the chapel of the Palacio Nazarenas. He has worked at Belmond’s properties across Peru for 22 years.

Offshoots of Tawantinsuyu’s aristocracy still live in Cusco. Alfredo Inca Roca, a descendant of the Inca Viracocha, has donned a golden costume eight times to play the Inca in Inti Raymi – the midwinter Festival of the Sun, revived in 1944.

Alfredo Inca Roca gestures to the ears of corn grown on his smallholding not far from Cusco. Peru today boasts 55 varieties of corn – from white to golden and purple – painstakingly improved by Inca agronomists, Alfredo’s ancestors.

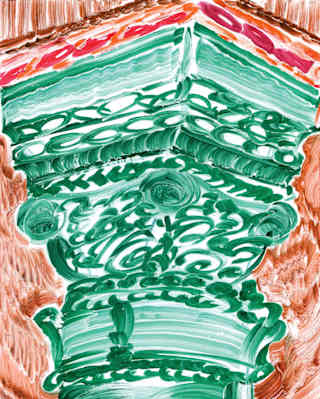

The column that adorns the Nazarenas Suite. Though carved in classical Ionic style, the pillar is made of the dark volcanic stone characteristic of Inca temples.

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

Beaches, by Belmond

January is a month for rest, rejuvenation and dreaming of sun-soaked escapes. From iconic coastlines to hidden shores, these are the world’s most beautiful beaches – experienced the Belmond way.

Hello From the World’s Highest Beach

Most beaches meet the sea, however, this one greets the sky. Stake your spot at Collata Beach on Lake Titicaca’s Taquile Island, where Belmond’s Andean Explorer is offering a rare trip to the shore at an altitude of nearly 4,000 metres.

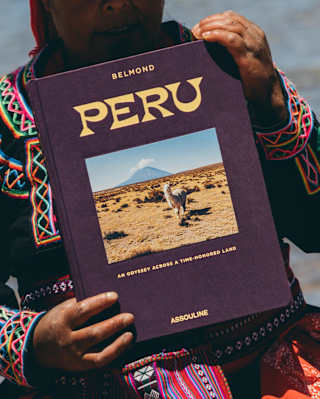

Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land

In this extract from “Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land,” a new book published by Assouline in collaboration with Belmond, journalist Catherine Contreras reveals a Peru travel guide, inviting readers to explore one of the planet’s most captivating destinations and showcasing the beauty of the locations where Belmond’s hotels and trains are found throughout Peru.

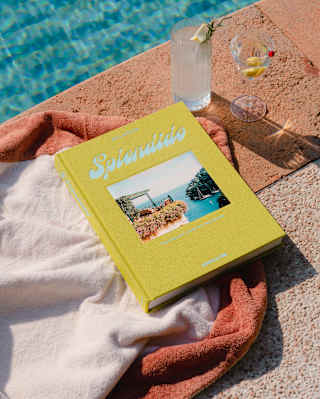

Splendido: The Radiant Stage of Portofino

For the new Belmond Assouline travel book, British journalist Matthew Bell dives into the history of Splendido to tell us the tales of the gem of the Italian Riviera. The hotel, which has entered a new chapter on the radiant stage of Portofino after a painstaking renovation, transforms into a mythical legend in the new Assouline travel book – discover an excerpt from the guide and read about the secret stories behind the iconic destination.

Go with the Slow: The Rise of Train Travel

Belmond continues to shape the future of luxury train travel, marked this year by the arrival of the Britannic Explorer, the first train of its kind in England and Wales. Monisha Rajesh – author of four travel books including ‘Moonlight Express: Around the World by Night Train’ – discovers why slow travel is having a resurgence.

Quite the Site: Luxury Travel to UNESCO World Wonders

As proud custodians of historic properties near cultural and natural wonders, Belmond’s hotels and trains are the perfect choice for travellers with a historical hankering. Whether you’re marvelling at the ingenuity of the ancient Romans in Britain or the wonders of the Mayas in Mexico, our properties are your gateway to the past.

Belmond Legends: Copacabana Palace

Welcome to Copa, the legendary stage for the most glamorous encounters and iconic revellers. This is the place where Rio entertains and enchants. The place where Rio starts.