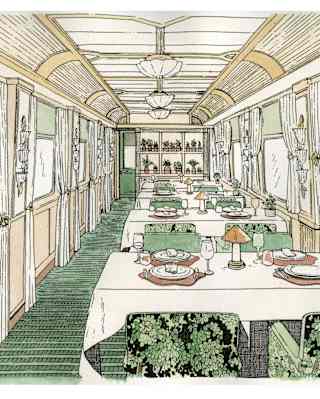

What to Wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express

It’s the one place in the world where it’s impossible to be overdressed. Style expert Osman Ahmed reveals her top tips on what to wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express train, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.

Read more - What to Wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express Where Nature Blossoms into Art

Discover how artist Anna Deller-Yee reinterprets Belmond’s iconic gardens – from bergamot to jasmine – in a limited-edition festive candle and trinket tray celebrating global biodiversity.

Read more - Where Nature Blossoms into ArtHello From the World’s Highest Beach

Most beaches meet the sea, however, this one greets the sky. Stake your spot at Collata Beach on Lake Titicaca’s Taquile Island, where Belmond’s Andean Explorer is offering a rare trip to the shore at an altitude of nearly 4,000 metres.

Read more - Hello From the World’s Highest BeachAnd The Winner Is…

The Belmond Photographic Residency, now in its second year, has crowned a new winner. Meet Tara L. C. Sood and her award-winning submission.

Read more - And The Winner Is… The Wedding Trends Defining 2026

Planning your big day? Weddings in 2026 are moving beyond tradition to embrace celebrations that are personal, meaningful and effortlessly elegant. From intimate beach elopements to sophisticated Art Deco-inspired soirées, discover the top trends for next year – each paired with the perfect Belmond venue.

Read more - The Wedding Trends Defining 2026The Great British Sunday Roast

The Brits’ love of a Sunday Roast has survived rationing and the rise of fads and food trends to carve out a place at the very heart of British culture. Discover the history of our national love affair with the Sunday Roast, and where to find the very best in London.

Read more - The Great British Sunday Roast Recipe: Enchiladas del Portal

While the term ‘enchiladas’ covers a wide range of flavour combinations with infinite permutations of stuffings and toppings, this version uses Guajillo chillies for a beautifully smoky flavour and sweet heat, which combines perfectly with cinnamon and cumin – the ultimate Mexican comfort food.

Read more - Recipe: Enchiladas del PortalPeru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land

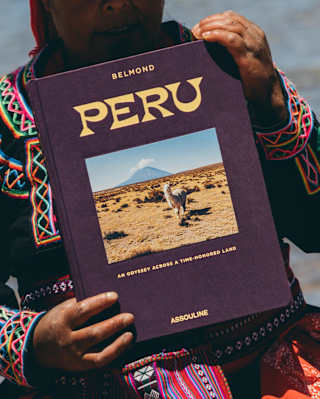

In this extract from “Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land,” a new book published by Assouline in collaboration with Belmond, journalist Catherine Contreras reveals a Peru travel guide, inviting readers to explore one of the planet’s most captivating destinations and showcasing the beauty of the locations where Belmond’s hotels and trains are found throughout Peru.

Read more - Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land Eat Your Way Through El Bajío

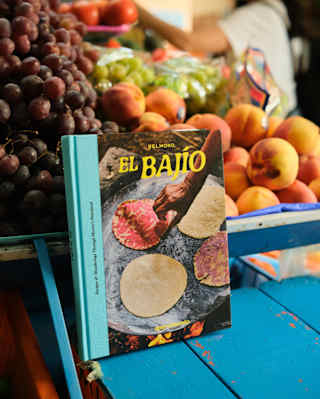

Discover ‘El Bajío: Recipes & Wanderings Through Mexico’s Heartland,’ the fourth cookbook in the collaborative series between Belmond and Apartamento.

Read more - Eat Your Way Through El Bajío