Ground Force

Ground Force

Discover how Mexico’s long-held tradition of transforming natural materials into craft is being respun by socially minded designers.

Having travelled around the country to get to the grassroots of the locally driven Mexican design scene, Darcie Imbert profiles the closed-loop creators whose fantastical objects and innovative projects are making a difference – while also reaching a global audience.

The creative energy of Mexico is no secret, and it’s by no means coincidental. To understand it fully you have to peel back layers of Mesoamerican history. To feel it, however, simply spend a weekend anywhere in Mexico, watching, tasting and talking.

Stories are found on every corner, in every conversation and with every bite. What roots it all is the appreciation of nature; it connects the ancient with the present and links Indigenous communities with contemporary creatives. With thousands of years of agricultural traditions passed down by the Aztecs and Mayans, looking to the land is woven into the very fabric of the country. For some cultures, this is sustainability; for others, it’s a way of life. To quote Mexico City-based designer Fernando Laposse, “Mexico is not a place for precision and steel; it’s a place for understanding how a plant will bend and not forcing it to be straight.” Mexico’s reliance on the environment has put regenerative thinking at the centre of its collective mindset. Today, designers, architects and craftspeople are reinterpreting ancestral ideas for the future.

CROP CIRCLES

To look at, Fernando Laposse’s creations are a playful show of texture and colour – furry beasts dyed hot pink using insects and sisal dogs that double up as benches – but the final product is just a small part of the story. Talking about the impact of nature on Mexican creativity, Laposse suggests its people and products are a direct expression of the land. “I am a big believer in the territory not as mere geography, but more as the term the French use to describe the location attributes that go into making a good wine: the terroir.” He continues, “Think of Mexico’s design terroir, it’s very much based on earth matter. Simply put, we are good at working with plants, clay and stone, and this translates into weaving techniques, ceramics and textiles.”

Laposse’s creations transform humble materials into refined design pieces, whose positive impact is felt at every stage. For one project, he developed totomoxtle, an innovative veneer made using the husks of heirloom Mexican corn, which comes in some 60 varieties ranging from rich purple to milky cream, and is under threat from GMO seeds and large scale agro-industrial operations. Developing this new craft has created incentives for these small-scale farmers to continue their agricultural traditions, generating income for them and playing a part in preserving biodiversity for future food security. “Design can be a lifeline to inject other forms of revenue,” says Laposse, “the key is to find a balance between tradition and innovation.” This is a project where everything is used: his team provides seeds to the Tonahuixtla community in the state of Puebla and when the corn is harvested the farmers keep the grain for their families, while a group of local women are paid to transform the husks into totomoxtle. It’s a circular dynamic, with the food that feeds people in the area a byproduct of the process. In other projects, Laposse works with agave fibres or dyes made from avocado pits and flowers, and around him everybody wins: industries innovate, communities thrive and nature is restored.

ZEROING IN ON WASTE

On the outskirts of Querétaro, Caralarga is a textile workshop that uses raw cotton thread and discarded textile waste as its medium. Founders Ana Holschneider and Ariadna García arrived at the idea by chance. Holschneider and her husband Luis González had taken over part of what was El Hércules textile factory complex to start a brewery. While building work was going on, Holschneider came across piles of fabric and thread that were destined to be thrown away. At first she and García spun it into earrings, now Caralarga employs 60 local artisans turning out huge tasselled wall-hangings, intricately tufted artworks and oversized cotton chandeliers, alongside jewellery and clothing, stocked in the boutique at Maroma, A Belmond Hotel, Riviera Maya, a luxury hotel on the Yucatán peninsula. Lapped by the Caribbean sea and a stone's throw from Playa del Carmen, this five star resort houses its own boutique dedicated to the finest Mexican luxury labels and hand-made local craft.

Though the Caralarga concept has grown, their commitment to celebrating the land remains the same. “In Mexico, it’s impossible to separate artisanal work from the land, since it provides the materials that are worked into creations,” says Holschneider. Many of the pieces produced by Caralarga are inspired by symbols of Mexican culture, including agriculture and nature – for example, a series of large format wall-hangings made from raw cotton with names such as Frijol (bean), Campo de Arroz (rice field) and Colmena (hive). All tying a sustainable thread between the natural world, industry and Mexico’s artisan heritage.

SPACES TO THINK

It’s more than colour that sets Mexican architecture and design apart. Dating back to the pre-Hispanic times, a patchwork of influences forms an architectural language that’s entirely unique and reveals that the notion of building sustainably is not new. The Mayan civilisation was a pioneer of urban planning, centring cities around family units that each had their own permaculture plot. Good architecture is about much more than structure and space; it is about creating something that brings communities together and restores the surrounding environment.

For Mexico City-based architect Gabriela Carrillo, the answer isn’t always a building. She explains that strong isn’t necessarily smart and permanent structures aren’t always the best solution; sometimes green spaces and ephemeral architecture are a better fit. Carrillo’s recent project with Colectivo C733 at the Bacalar Lagoon is a testament to her context-first approach. The lagoon is home to the world’s largest freshwater bacterial reef, but faces threats from urbanisation and human activity. The brief was to encourage visitors to connect with the ecosystem without damaging it. Floating atop the lagoon, this ecopark bends the parameters of what we consider architecture. The “building” was designed as a square-shaped pier, which at points rises to seven metres to clear dense mangrove, then drops to centimetres above the water. Below the walkways there is a research lab and, above, a museum exhibit serves as an educational hub. The pier minimises its impact on the ground and is oriented north, similar to many pre-Hispanic structures that had a profound awareness of the relationship between the earth, the sun and the stars.

This is an abridged version of this article. To read in full, pick up a copy of Mondes magazine at your next stay with Belmond.

Photographs: Sisal monster by Fernando Laposse, Muelle San Blas, a Colectivo C733 project (Albers Studio), sisal benches in Archivo Transmutaciones by Fernando Laposse, Campo de Arroz piece by Caralarga, Fernando Laposse in a corn field, sculptural hammock by Fernando Laposse in collaboration with textile designer Angela Damma (Pepe Molina).

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

The Wellness Trends to Travel For in 2026

From longevity retreats and contrast therapy to ancient ceremonies and community-led healing, these are the wellness travel trends redefining how, why and where we journey in 2026.

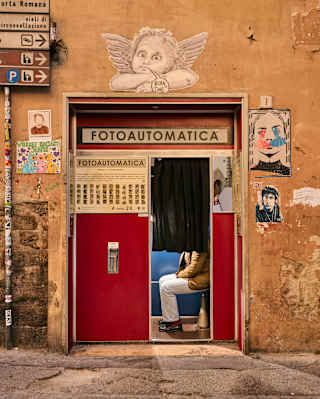

An Insider’s Guide to Florence

While Florence has one foot rooted in Renaissance splendour, the other strides out into a future filled with some of the world’s finest food, music and fashion. Make your base at Villa San Michele, then explore our guide to the city’s best kept secrets.

Interview: Meet Thebe Magugu

Thebe Magugu is one of South Africa’s most celebrated fashion designers and he’s now making his first foray into interior design at Belmond’s Cape Town landmark, Mount Nelson. We sat down with the prolific polymath to hear about the care and craft behind his suite design, as well as his vision for a new cultural institute to sit alongside it.

What to Wear in the Mexican Caribbean

There is something about a tropical climate that instantly lifts your mood – so dress to match your serotonin levels. Style expert Osman Ahmed leads us through the do’s and don’ts of a tropical holiday to the Caribbean coast of Mexico, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.

The Gelato of Madeira

Discover how the team at Reid's Palace, Funchal, transposed the island’s abundance of tropical fruits and liqueurs into the perfect scoop at Gelateria San Giorgio.

Recipe: Esquites with Marrow

A touch of decadence in a single-serving cup, these esquites with bone marrow are a reminder that Mexican street food doesn’t always need to be minimal or pure – it can also be fun, a little wild and exactly what you want when the day gets too serious.

Where Nature Blossoms into Art

Discover how artist Anna Deller-Yee reinterprets Belmond’s iconic gardens – from bergamot to jasmine – in a limited-edition festive candle and trinket tray celebrating global biodiversity.