Deià Gratias

Deià Gratias

Mallorca’s rich island cuisine is enjoying a remarkable renaissance as visitors discover its abundant produce—and a cuisine that’s becoming increasingly refined.

Deià was my day one; where it all started. This village on the picture-perfect north coast of Mallorca was where, as a student, I arrived on the bus from Palma and stayed for a summer.

In those days—the late 1980s—Deià was a low-rent Bohemian hangout and a very different place from the polished and luxurious enclave it has since become. The village was my introduction to the Spanish lifestyle and, not least, to real Spanish food. At the pension that was my home that summer, I ate my first proper paella, fragrant with saffron and garlic. My first experiences of typical ‘cuina mallorquina’—Mallorcan cooking—also happened here in the simple village restaurants that served up vegetable ‘tumbet’ and ‘sopes mallorquines’, a kind of soupy stew with bread. On hot summer days I bought slabs of ‘coca’—the Spanish take on pizza, loaded with roasted vegetables and sometimes a sardine or two—from the village bakery in Deià and headed for the beach with a can of cold beer.

I had some good times and some good food. Even so, looking back over three decades of eating on Mallorca, it's hard to deny that things have changed for the better. Sure, the 1980s provided plenty of opportunity for cheap and cheerful eating. But these days, food on the island is some of the most varied and excellent in Spain. Influences have come from the mainland, from across the Mediterranean to enrich a once-parochial scene. Fusion food and contemporary cuisine have made their mark and it’s surely a sign of something that Mallorca now boasts a total of seven Michelin stars, three of which belong to island-born chefs.

There are various fronts to this revolution. One is the new wave of Mallorcan wines, which have leaped ahead since the days when island wine lists majored on Rioja. Wines are made—often from local grape varieties such as Manto Negro and Callet—at more than 70 wineries across the island. Another is the huge popularity of tapas. Recently the “little dishes” of mainland Spain and the shared informality they engender, have taken the island by storm.

Perhaps the biggest change, however, is the rediscovery of traditional Mallorcan food by the islanders themselves. Possessor of a mighty tourist industry, the island had little time to ponder its own arcane traditions as it worked to satisfy the food requirements of its visitors. But a new interest in Mallorcan culture has brought once-forgotten local recipes back to island menus. You are much more likely to find traditional dishes such as the chicken stew ‘escaldums’ or ‘arrós brut’ (a powerful winter dish of mixed meats and rice, spiced with cinnamon and pepper) than at any time in the past 30 years. Pastry shops in Palma now sell sweetmeats, such as potato buns and ‘redonets de Santa Clara’, that had all but fallen into extinction. Even the classic ‘ensaimada’, a delicious whorl of pastry made unctuous with pork fat and dusted with icing sugar, is once more being made according to an authentic 300-year-old recipe at bakeries such as Palma's Fornet de la Soca.

It’s a global phenomenon: increasingly, 21st-century consumers want traceable foods they can trust. The locavore—the locally-produced food movement—has its equivalent on Mallorca, where there has always been some classy produce. The Slow Food organisation, which has a chapter here, has also brought about a renewed awareness of unique local varieties such as the Mallorcan red sheep—from which a superb raw-milk cheese is made by Llorenç Payeras in Lloseta—and xeixa wheat, brought back into widespread cultivation by Pollença-based bakers Tomeu Morro and Biancamaria Riso. There has, too, been a surge of interest in island-made olive oils. As of this year, Mallorca finally has its own Denominación de Origen for olive oil, signalling the triumphant return of a product made on the island since the Arabs first planted olives here in the 10th century.

Mallorca is often described as more like a continent than an island, such is its variety in landscapes, from the olive groves of the Tramuntana mountains to the fertile agricultural land of Sa Pobla (home of the increasingly popular Sa Pobla potato) and the salt flats of Es Trenc. Varied geography means varied produce and the range of island ingredients would make for a groaning kitchen table.

What would I single out, then, among all this Balearic bounty? Certainly the sweet, oil-rich Marcona almonds and the luscious apricots of Porreres, in season during early summer. Also the figs and melons, the sunshine-bright and sensationally scented Sóller lemons, the ramallet tomato—typical of the island, often seen hanging in bunches to last throughout the winter—and the paprika-like ground red pepper from the once-rare Tap de Cortí variety. In another tale of rescued food, a German businesswoman has revived the artisan process of salt-making on the island to produce Flor de Sal d'Es Trenc—some of the finest sea salt to be found anywhere. I can never leave Mallorca without a tub of Flor de Sal—either au naturel or in a range of flavourings including lemon and chilli, black olive or hibiscus.

As you’d expect from a Mediterranean island, the fish and shellfish here are the best and the king of local fish counters is surely the Sóller prawn. There is nothing in the world quite like this deep-red, juicy prawn, best served a la plancha (grilled) and sprinkled with flakes of Es Trenc salt.

But if there's a single speciality central to the island's culinary identity, it has to be ‘sobrassada’. No self-respecting Mallorcan fridge or larder is complete without the bulbous shape and buff orange colour of this unique sausage, ideally made from ground pork meat from the ‘porc negre’ (black pig) breed, generously spiced with ‘pimentón’ for a pungent flavour.

‘Sobrassada’ is commonly eaten alongside country bread rubbed with tomato and drizzled with olive oil—the Mallorcan favourite ‘pamboli’ (literally 'bread with oil')—or spread as you might a paté on the salty biscuits made by Quely. Island chefs use ‘sobrassada’ in sauces or as part of a stuffing—I’ve even seen it grilled in thick slices and drizzled with honey.

Recently I returned to Mallorca, whose charm never fades despite its increasing sophistication. I found Palma prettier than ever, its streets cleaner and more prosperous, with chic restaurants and smart hotels. Always a fan of the food markets, I headed to the Mercat de l’Olivar with its kaleidoscopic view of everything that is best in Mallorcan produce, from ‘porc negre’ to Es Trenc salt. But I found there was a new contender for my foodie cravings.

The San Juan Gastronomic Market represents a new breed of food market—pioneered by Madrid’s Mercado de San Miguel and Mercado de San Antón—which adds value to top-quality Spanish ingredients by presenting them as high-class tapas to be enjoyed in situ. The S’Escorxador building, dating from 1905, was once a slaughterhouse: in its revamped and gastro-fabulous form, it now embraces tapas bars, a cocktail bar, terraces for schmoozing and a kitchen space for public use, called Cooking 4 People. I spent a happy lunchtime perusing the market’s tapas offer, enjoying a Basque pintxo in one stall, a plate of sushi in a second and a dozen oysters with a glass of cava in a third.

Next day, feeling nostalgic for my student days, I hired a car and drove north to the Tramuntana coast, cruising its switchback roads in the morning sun with the sea sparkling below. It was along the narrow road from Sóller, I recalled, that the bus had first brought me to Deiá all those years ago.

When I was a teenager, the common prejudice was that Mallorca was nothing more than bucket-and-spade territory, typified by the boisterous resorts of Magaluf and s’Arenal. If any single thing has altered the way we perceive the island as a destination, it’s probably La Residencia, A Belmond Hotel, Deià. This grande dame of Mallorca’s country-house hotels has transformed Deià into an oasis of rural chic.

Since I first gazed up at it longingly in 1985, the hotel has grown and matured. Its olive groves, unloved for decades, are now perfectly tended and the estate is now producing its own olive oil. Part of the hotel’s philosophy is that guests should experience something of the island’s traditional rural ways. Currently among its most popular activities is a walk through the olive groves towards a mountain refuge with views over the village where a lavish picnic awaits, including rustic specialities ‘pambol’, ‘sobrassada’ and ‘camaiot’, the savoury turnovers called ‘cocarrois’, home-cured olives and ‘ensaimada’ stuffed with ‘crema catalana’.

That night I dined at its El Olivo restaurant, housed in the former olive mill of the stone mansion where chef Guillermo Méndez, a local boy from Sóller, has crafted a luxurious menu. But the roots of Mallorcan tradition are here, sure enough. Mendez’s loyalty to local produce means that on the menu are Sóller prawns with olive oil, roast island lamb with rosemary and local suckling pig with sage and ‘sobrassada’ sauce. The chef uses Porreres figs and Mallorcan oranges and homemade rustic bread. His creamy rice dish made with Sa Pobla rice, wild mushrooms and quail breasts wiped the floor with my student paella that summer in Deià.

For as long as I can remember, Mallorca’s traditional food and authentic local ingredients have fascinated me. But now, I realise I’m not the only one.

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

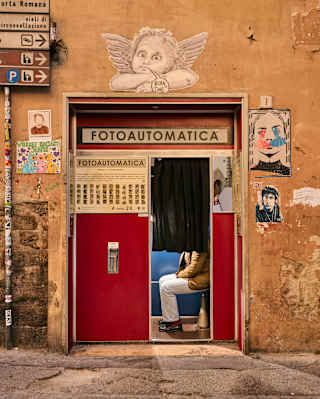

An Insider’s Guide to Florence

While Florence has one foot rooted in Renaissance splendour, the other strides out into a future filled with some of the world’s finest food, music and fashion. Make your base at Villa San Michele, then explore our guide to the city’s best kept secrets.

Interview: Meet Thebe Magugu

Thebe Magugu is one of South Africa’s most celebrated fashion designers and he’s now making his first foray into interior design at Belmond’s Cape Town landmark, Mount Nelson. We sat down with the prolific polymath to hear about the care and craft behind his suite design, as well as his vision for a new cultural institute to sit alongside it.

What to Wear in the Mexican Caribbean

There is something about a tropical climate that instantly lifts your mood – so dress to match your serotonin levels. Style expert Osman Ahmed leads us through the do’s and don’ts of a tropical holiday to the Caribbean coast of Mexico, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.

The Gelato of Madeira

Discover how the team at Reid's Palace, Funchal, transposed the island’s abundance of tropical fruits and liqueurs into the perfect scoop at Gelateria San Giorgio.

Recipe: Esquites with Marrow

A touch of decadence in a single-serving cup, these esquites with bone marrow are a reminder that Mexican street food doesn’t always need to be minimal or pure – it can also be fun, a little wild and exactly what you want when the day gets too serious.

Where Nature Blossoms into Art

Discover how artist Anna Deller-Yee reinterprets Belmond’s iconic gardens – from bergamot to jasmine – in a limited-edition festive candle and trinket tray celebrating global biodiversity.

What to Wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express

It’s the one place in the world where it’s impossible to be overdressed. Style expert Osman Ahmed reveals her top tips on what to wear on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express train, as part of our ‘Location Dressing’ series.