Bloom Time

Bloom Time

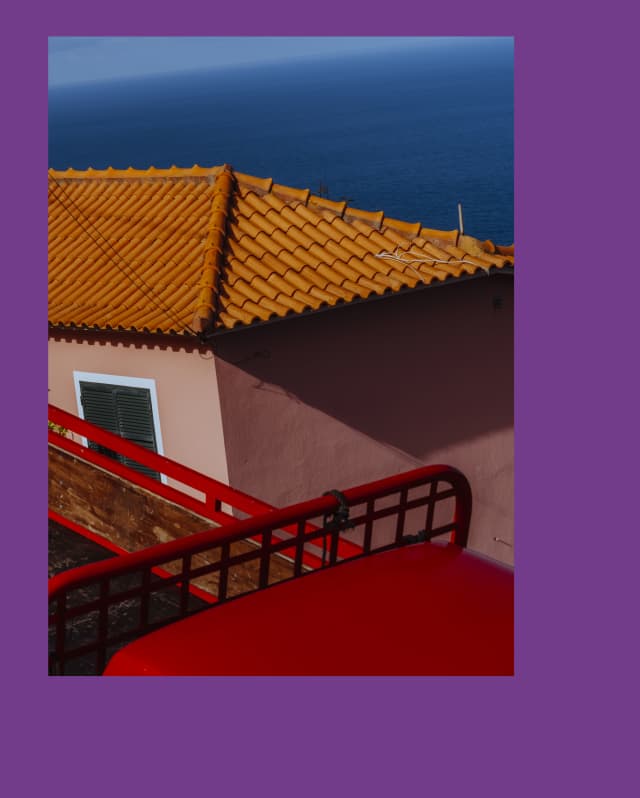

Madeira is shaped by water – from the high-rolling waves of the coast to the hillside levadas that funnel rainfall down to secret gardens. Rick Jordan dives in, with photography by Maximilian Virgili.

Madeira has a relationship with water unlike any other place in the world. It seeps out of hillsides and bounds down cliffs, ripples around irrigation channels and, of course, surrounds the island itself, swelling and throwing itself into jagged rocks and basalt black beaches. In some places in the world, water is voluptuous and soft; but on Madeira it feels dynamic, assertive, filled with purpose. And most of that water comes from the cloud forest. Oculto precipitas, as the islanders refer to it: hidden rainfall.

Twenty million years ago, when giant crocodiles and sharks swam in seas and rivers, much of southern Europe was covered by laurel forest, or laurissilva. That retreated over the millennia, but remains on the Azores, the Canaries and Madeira, where it covers much of the high interior and northern coast. Those glossy evergreen leaves comb the low clouds, brushing droplets down branches and into the soil, seeping into underground channels and reservoirs. If the laurissilva has a poster child, it’s the forest at Fanal, a ghostly plateau where cows graze among crooked, centuries-old trees, a veil of mist smudging the senses. Another plateau acts as a natural reservoir, collecting water each rainfall; the road across it is raised up by a couple of feet, so it feels like driving on a causeway across a curious mountain lake.

When the previously uninhabited island was first settled in the 15th century, the Portuguese began irrigating the land to grow sugarcane and grapes, cutting tiny canals, or levadas, into the hillside to let the water flow down. These were added to over the years, with narrow pathways running alongside in order to maintain them, inadvertently creating the hiking trails of the present day, which lead all over Madeira. I’ve walked levadas with my young son, assembling primitive boats from banana leaves and sticks to send sailing wonkily down. Some lead across farmland, most take you high and deep into the subtropical forest, where creepers hang and camellias bloom, to lagoons that can be waded and plunged into.

Brushing my hand over a vertical rockface of moss, lichen and ferns, water oozing out to join the levada flowing below, I wonder if the person who came up with the idea of architectural living walls of plants had ever visited the island. On my latest visit, in early winter, I’m taken by a guide to a route less trodden – Levada do Moinho – following the narrow pathway above a precipitous drop, nervously watching my footsteps one by one, until it leads us through a green-furred grotto and behind two waterfalls, jetting down to the pool below.

Trickle down, trickle down. “There are water thieves around, you know,” market gardener Sofia Freitas tells me, as she squints into the November sunlight. Freitas manages the land in Quinta da Palmeira, growing produce for José Diogo Costa, the executive creative chef at Reid’s Palace, A Belmond Hotel, Madeira, along with a few other restaurants on the island. “We’re allowed 12 hours of levada water a week,” she explains. “You lift the shutter at a certain time so we can irrigate the crops. It’s a system that works well, but there are always some people who take advantage...” She shows me around, swishing through high grass to uncover strawberries and Brazilian horseradish growing beneath. “We have a lot of weeds – nature doesn’t have bare soil, does it? The first rule here is: don’t be afraid to stand on things,” she laughs. She describes how herbs are fermented, “which we add to the water so she has more nutrients”. So water’s female? I ask, half-jokingly. “Of course,” comes the matter-of-fact reply, “she brings life.”

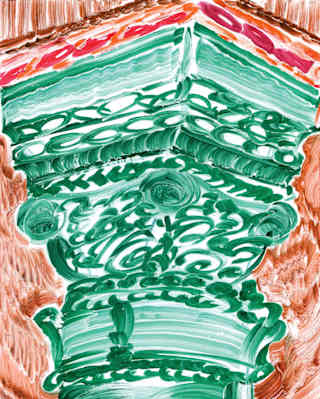

The volcanic soil of Madeira is almost indecently fertile. Things grow quickly here. At Quinta da Palmeira, that means pumpkins, broccoli and tomatoes, aubergines and fennel. Walk around the market and you’ll see some of the sheer diversity: the strange pineapple-banana, whose crocodile skin crumbles off when it’s ripe; passion fruit in pool-table colours; tomato-like tamarillo. Chef Costa holds a handful of bright red Surinam cherries and tells me they’re a favourite on his menu at William Restaurant in Reid’s Palace. There he digs deep into the island’s food traditions, using sugarcane and berries in sweet and savoury dishes, as well as smoked bay leaf, dried tuna and fennel. All around Funchal, water channels help irrigate Edwardian gardens such as the one at Reid’s Palace, planted more than a century ago when Madeira’s climate made it a laboratory for plant collectors – Mexican cacti here, a South African bird of paradise there, the spires of red aloe and yellow flowers of the popcorn plant below the tall trunks of cedars and Canary Island date palms.

Back down at the shore, the sea bed falls away sharply – these are deep waters, quickly reaching the evocatively named Twilight Zone at 200 meters before plunging into the Midnight Zone at 1,000. Strange beasts emerge from the depths, such as giant squid and the black scabbard fish, a fearsome creature whose appearance belies its taste, and is featured on every menu in town.

At Reid’s Palace, down among tumultuous black rocks at the seaside lido, there is a diving board that juts out almost surreally above jangled waves. The sea is too rough to jump in, but the tidal pool has been here as long as the hotel, and I swim to and fro, pausing every so often to watch the velvety red crabs that scuttle on the rocks around me, pincers like chopsticks as they feed, impervious to the foaming surf breaking over them.

Sea swimming on Madeira is part of daily life; it feels redolent of the heroic age of the sport, when Byron swam the canals of Venice and Rupert Brooke skinny-dipped with Virginia Woolf in Grantchester. The walls of Reid’s Palace are lined with vintage photographs of lithe figures performing elegant swallow dives off rocks.

On my last day on Madeira, I hitch a ride on a friend’s boat for a sunrise cruise and we sail eastwards out of Funchal, the only people on the water at 6:30am. A few kilometers along the coast we stop and I jump overboard, the water initially cool on my skin. Floating on my back, I look up at the island, rising like a benign Godzilla from the waves, the early light bathing its green contours gold. Once again, the view looking inward as mesmerizing as the ones looking out to sea.

This is an abridged version of this article. To read in full, pick up a copy of Mondes magazine during your next stay with Belmond.

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

Beaches, by Belmond

January is a month for rest, rejuvenation and dreaming of sun-soaked escapes. From iconic coastlines to hidden shores, these are the world’s most beautiful beaches – experienced the Belmond way.

Hello From the World’s Highest Beach

Most beaches meet the sea, however, this one greets the sky. Stake your spot at Collata Beach on Lake Titicaca’s Taquile Island, where Belmond’s Andean Explorer is offering a rare trip to the shore at an altitude of nearly 4,000 metres.

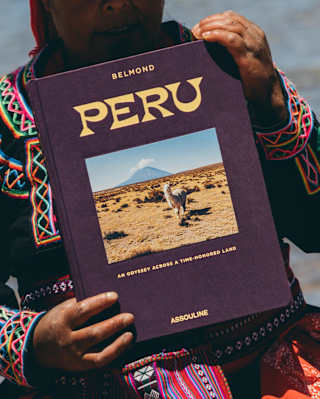

Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land

In this extract from “Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land,” a new book published by Assouline in collaboration with Belmond, journalist Catherine Contreras reveals a Peru travel guide, inviting readers to explore one of the planet’s most captivating destinations and showcasing the beauty of the locations where Belmond’s hotels and trains are found throughout Peru.

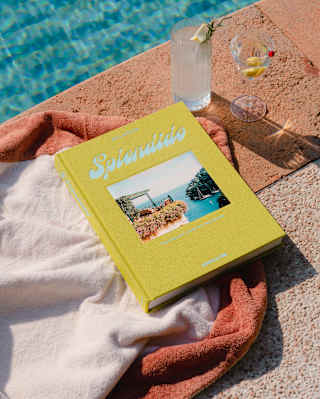

Splendido: The Radiant Stage of Portofino

For the new Belmond Assouline travel book, British journalist Matthew Bell dives into the history of Splendido to tell us the tales of the gem of the Italian Riviera. The hotel, which has entered a new chapter on the radiant stage of Portofino after a painstaking renovation, transforms into a mythical legend in the new Assouline travel book – discover an excerpt from the guide and read about the secret stories behind the iconic destination.

Go with the Slow: The Rise of Train Travel

Belmond continues to shape the future of luxury train travel, marked this year by the arrival of the Britannic Explorer, the first train of its kind in England and Wales. Monisha Rajesh – author of four travel books including ‘Moonlight Express: Around the World by Night Train’ – discovers why slow travel is having a resurgence.

Quite the Site: Luxury Travel to UNESCO World Wonders

As proud custodians of historic properties near cultural and natural wonders, Belmond’s hotels and trains are the perfect choice for travellers with a historical hankering. Whether you’re marvelling at the ingenuity of the ancient Romans in Britain or the wonders of the Mayas in Mexico, our properties are your gateway to the past.

Belmond Legends: Copacabana Palace

Welcome to Copa, the legendary stage for the most glamorous encounters and iconic revellers. This is the place where Rio entertains and enchants. The place where Rio starts.