How 500 Brushstrokes Become One

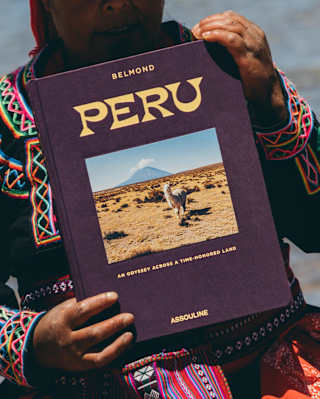

“Human encounters are truly magical.” In an era shaped by artificial intelligence and rapid technological change, this reflection by Chinese artist Wu Jian’an feels quietly radical. It also serves as the emotional core of 500 Brushstrokes in Peru, his ambitious travelogue and participatory art project, soon to be exhibited at Art SG Singapore.

Read more - How 500 Brushstrokes Become OneThe Artisans Reimagining Florence’s Finest Hotel

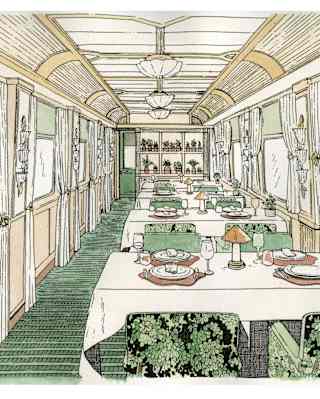

Italy’s ultimate retreat and Renaissance haven, Villa San Michele occupies a privileged perch on the hills overlooking Florence. Set within the original monastery and gardens, every space is designed to deepen the connection to Florence’s breathtaking landscape and rich culture. Discover the artisans reviving this Renaissance legend, reopening in Spring 2026 after a complete renovation.

Read more - The Artisans Reimagining Florence’s Finest Hotel Recipe: Esquites with Marrow

A touch of decadence in a single-serving cup, these esquites with bone marrow are a reminder that Mexican street food doesn’t always need to be minimal or pure – it can also be fun, a little wild and exactly what you want when the day gets too serious.

Read more - Recipe: Esquites with MarrowBeaches, by Belmond

January is a month for rest, rejuvenation and dreaming of sun-soaked escapes. From iconic coastlines to hidden shores, these are the world’s most beautiful beaches – experienced the Belmond way.

Read more - Beaches, by Belmond