The Wedding Trends Defining 2026

Planning your big day? Weddings in 2026 are moving beyond tradition to embrace celebrations that are personal, meaningful and effortlessly elegant. From intimate beach elopements to sophisticated Art Deco-inspired soirées, discover the top trends for next year – each paired with the perfect Belmond venue.

Read more - The Wedding Trends Defining 2026The Great British Sunday Roast

The Brits’ love of a Sunday Roast has survived rationing and the rise of fads and food trends to carve out a place at the very heart of British culture. Discover the history of our national love affair with the Sunday Roast, and where to find the very best in London.

Read more - The Great British Sunday Roast Recipe: Enchiladas del Portal

While the term ‘enchiladas’ covers a wide range of flavour combinations with infinite permutations of stuffings and toppings, this version uses Guajillo chillies for a beautifully smoky flavour and sweet heat, which combines perfectly with cinnamon and cumin – the ultimate Mexican comfort food.

Read more - Recipe: Enchiladas del PortalPeru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land

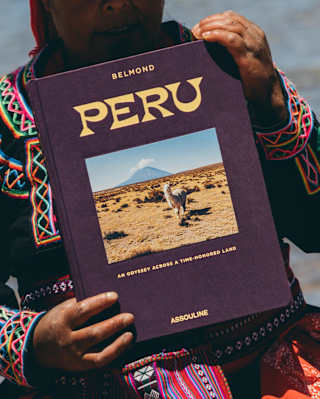

In this extract from “Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land,” a new book published by Assouline in collaboration with Belmond, journalist Catherine Contreras reveals a Peru travel guide, inviting readers to explore one of the planet’s most captivating destinations and showcasing the beauty of the locations where Belmond’s hotels and trains are found throughout Peru.

Read more - Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land Eat Your Way Through El Bajío

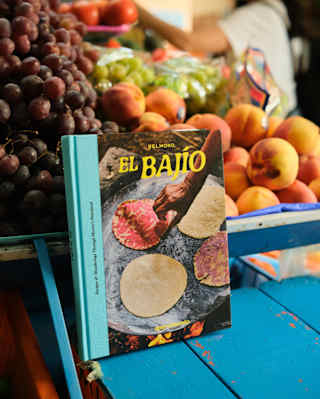

Discover ‘El Bajío: Recipes & Wanderings Through Mexico’s Heartland,’ the fourth cookbook in the collaborative series between Belmond and Apartamento.

Read more - Eat Your Way Through El Bajío Splendido: The Radiant Stage of Portofino

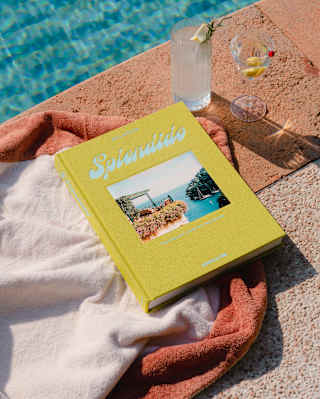

For the new Belmond Assouline travel book, British journalist Matthew Bell dives into the history of Splendido to tell us the tales of the gem of the Italian Riviera. The hotel, which has entered a new chapter on the radiant stage of Portofino after a painstaking renovation, transforms into a mythical legend in the new Assouline travel book – discover an excerpt from the guide and read about the secret stories behind the iconic destination.

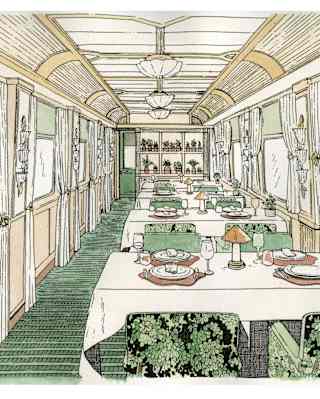

Read more - Splendido: The Radiant Stage of Portofino Go with the Slow: The Rise of Train Travel

Belmond continues to shape the future of luxury train travel, marked this year by the arrival of the Britannic Explorer, the first train of its kind in England and Wales. Monisha Rajesh – author of four travel books including ‘Moonlight Express: Around the World by Night Train’ – discovers why slow travel is having a resurgence.

Read more - Go with the Slow: The Rise of Train TravelQuite the Site: Luxury Travel to UNESCO World Wonders

As proud custodians of historic properties near cultural and natural wonders, Belmond’s hotels and trains are the perfect choice for travellers with a historical hankering. Whether you’re marvelling at the ingenuity of the ancient Romans in Britain or the wonders of the Mayas in Mexico, our properties are your gateway to the past.

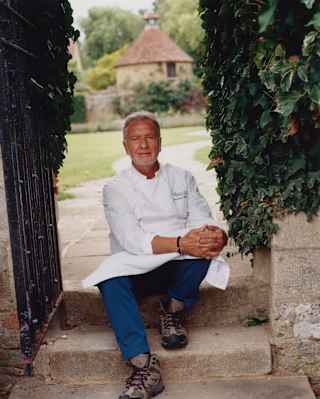

Read more - Quite the Site: Luxury Travel to UNESCO World Wonders 164 Seasons of Le Manoir with Raymond Blanc OBE

For 164 seasons spanning over 41 years, Chef Raymond Blanc OBE has pioneered garden-to-table gastronomy at Le Manoir aux Quat'Saisons in Oxfordshire. As we honour his legacy with his transition from Chef Patron to Founder and Lifetime Ambassador, we take a moment with him to look back at the last four decades of excellence, passion and joy.

Read more - 164 Seasons of Le Manoir with Raymond Blanc OBE