Feast of the Gods

Feast of the Gods

There’s barely been a food story in the past decade that doesn’t relate in some way to Mexico’s jungle larder. On a corn-popping road trip across the Yucatan Peninsula, Javier Arredondo celebrates the mamas who are paving the way forward.

All good meals in this part of Mexico start with sikil p’ak. The Yucatec answer to hummus is made with three staples of Mexican cuisine: pumpkin seeds, tomato and chilli. Firstly, pumpkin seeds are toasted until golden and crispy, then ground until very fine. This powder is mixed with a charred tomato salsa, a few drops of lemon juice and a touch of scorched habanero, creating a thick, earthy dip that is eaten with crispy tortilla chips. Every house and restaurant has their own version of sikil p’ak, each one more rich and savoury than the last.

Thinking about food in the Yucatan Peninsula is a good way to understand this unique and complex part of Mexico. It’s a place that deserves to be much more deeply explored than its famous coastal sweep, and whose many layers peel back to reveal seams of nature, history, architecture, and design, and of course traditional cuisine.

The Yucatan Peninsula is actually made up of three states: Yucatan and Quintana Roo – the coastal region encompassing Cancun and the Riviera Maya along which Maroma, A Belmond Hotel, Riviera Maya sits. Each state is home to distinct dishes that mix ingredients seen elsewhere in Mexican cooking such as corn, tomato, pumpkin and beans, with produce that is unique to the area such as chaya, habanero chilli, sour orange, and the popular red achiote seeds that provide colour and flavour.

Chaya is an ingredient that appears everywhere. A plant with maple-like leaves that grows all over the Yucatan, it has near-miraculous claims to its benefits: richer in iron than spinach, a powerful source of potassium and calcium, its uses range from preventing coughs to fighting arthritis. Chaya is the original Yucatec superfood. The leaves, however, are fairly bland so are often added to soups, sauces, salsas and salads. While smaller leaves might appear as a garnish, the larger ones are chopped and cooked for a long time. And for an ancient staple, chefs and mixologists seem to keep discovering new uses for it, with chaya-mezcal margaritas the most recent trend to appear on local menus.

This is a land full of legends and myths, stories and scientific theories. The oldest being that some 66 million years ago, a meteorite struck Earth in Chicxulub, northeast of Mérida. An event that produced a shock wave that radiated across the oceans, killed dinosaurs and left a giant crater with a radius of 180km. The debris that impacted the Yucatan in its wake is one of the theories for the formation of cenotes, the natural wells or reservoirs that were formed when the limestone surface collapsed exposing water underneath.

Every time I visit the Yucatan from Mexico City where I live, I find it fascinating that discoveries are still being made here: it was only in 2018 that the world’s largest underwater cave, 360km long, was found near Tulum. “This immense cave represents the most important submerged archaeological site in the world,” explains Guillermo de Anda, a National Geographic explorer and director of the Great Maya Aquifer project. “It has more than one hundred archaeological contexts, among which is evidence of the first settlers of America, as well as the extinct fauna and, of course, the Maya culture.”

Cenotes are unique to the Yucatan and one of the most fascinating things to do on the Riviera Maya, having historically been the major source of water used in Mayan rites over millennia. Today, some of these stunningly beautiful cave-like formations are public, while others are in private properties and some have even been intervened by artists such as James Turrell’s amphitheatre in Ochil.

One of the most beautiful cenotes I have swam in is Yaxunah: a cool deep pool of the clearest, vividest blue, surrounded by ancient native trees, whose roots reach down towards the water. Yaxunah is a small village of about 650 people that I would have never visited were it not for Rosalia Chay Chuc, a Mayan chef who creates authentic recipes and makes the region’s best cochinita pibil – a slow-cooked pork that is probably the most famous of Yucatec dishes. Yaxunah is about 25 minutes drive southeast of the vast ruined ancient city of Chichén Itzá, and has an important archaeological site of its own, an acropolis of three pyramids mostly covered by jungle and with barely any visitors; one of those rare secret places that you can still find throughout the Peninsula.

While crushing achiote seeds with her limestone roller, Rosalia tells me that several years ago Roberto Solis – the renowned chef-patron at Néctar restaurant in Mérida, known as the creator of the new Yucatecan cuisine – came to Yaxunah looking to buy pigs to prepare cochinita pibil. When Roberto tried Rosalia’s cochinita, he immediately recognised a brilliant chef and returned whenever he had friends visiting. One of whom was Danish Michelin-starred chef Rene Redzepi.

Redzepi also fell for Rosalia’s cooking and when he was asked by the Netflix TV show Chef’s Table to recommend interesting chefs around the world, Rosalia came to mind (she and other women from the village had previously worked with Redzepi at his Noma Mexico pop-up in Tulum in 2017). Rosalia’s family make cochinita pibil the traditional way; the same way it has been cooked for more than 1,000 years, which is to bury a pig in a steaming, smouldering, stone-lined pit and stew it very slowly in a heavy lidded pot with some water at the bottom, a process that requires patience and precision.

Rosalia started learning this ancestral craft at the age of eight under the guidance of her grandmother; first making tortillas, then graduating to preparing the recado (marinating paste) before becoming a master of the pib (underground oven). Today this is a job that her sons, Jesús and Filipe, do outside the family’s thatched palapa house, digging up layers of earth and peeling back banana leaves to reveal the pib where Chay’s cochinita pibil cooks for anywhere between 12 and 24 hours.

The pork has first been marinated by Rosalia and her sister Tere with a bright red recado of achiote seeds, garlic, spices and bitter orange juice, and then wrapped in banana leaves. Once the meat is tender, it is pulled and served simply in its own savoury, smokey juices with hot handmade tortillas and pickled onion

Three kinds of recado paste are commonly used in Yucatec cuisine: white, red or black, each based on Yucatec oregano, roasted garlic, cinnamon, pepper and clove. Achiote seeds are added to create the red version and chilli chagua or dry chile, which is charred to turn it black. Alternatively, this paste is often mixed with vegetable or chicken broth, but is also combined with sour orange juice to marinate the pork which is then grilled and sliced for poc chuc, another delicious classic dish served with pickled red onions and fresh tortillas. A tangy fish poc chuc version is often found on menus throughout the Riviera Maya.

Wherever you are on the Yucatan Peninsula, long-held tradition still courses through these lands. In Mérida that might be at La Chaya Maya, where families trade gossip over steaming plates of relleno negro (black turkey stew) served by staff dressed in hand-embroidered huipiles. While in the yellow-painted town in Izamal, about an hour west, that place is Kinich, which serves Yucatec food in a charming house a few blocks from the town’s monastery. Its much-loved classics such as the sopa de lima – a chicken broth with crispy tortilla julienne – and perfectly-made cochinita pibil with fresh tortillas draw locals from across the state.

And scooping from a bowl of sikil p’ak sitting in the garden here, it’s easy to see that Mayan cuisine isn’t just an edible history lesson, but a simmering dialogue between past and present.

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

The Novel That Defined Portofino

Portofino has been the backdrop for countless cultural moments, but one book from the 1920s is often credited with kickstarting the belle epoque of the Italian Riviera. Matthew Bell, contributing editor at Tatler, explores its enduring impact.

Beaches, by Belmond

January is a month for rest, rejuvenation and dreaming of sun-soaked escapes. From iconic coastlines to hidden shores, these are the world’s most beautiful beaches – experienced the Belmond way.

Hello From the World’s Highest Beach

Most beaches meet the sea, however, this one greets the sky. Stake your spot at Collata Beach on Lake Titicaca’s Taquile Island, where Belmond’s Andean Explorer is offering a rare trip to the shore at an altitude of nearly 4,000 metres.

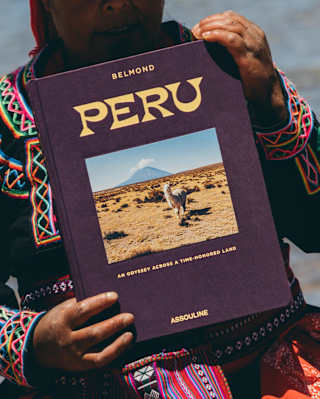

Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land

In this extract from “Peru: An Odyssey Across a Time-Honoured Land,” a new book published by Assouline in collaboration with Belmond, journalist Catherine Contreras reveals a Peru travel guide, inviting readers to explore one of the planet’s most captivating destinations and showcasing the beauty of the locations where Belmond’s hotels and trains are found throughout Peru.

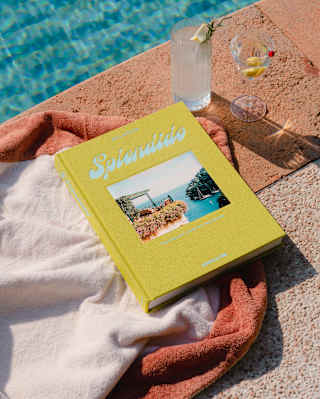

Splendido: The Radiant Stage of Portofino

For the new Belmond Assouline travel book, British journalist Matthew Bell dives into the history of Splendido to tell us the tales of the gem of the Italian Riviera. The hotel, which has entered a new chapter on the radiant stage of Portofino after a painstaking renovation, transforms into a mythical legend in the new Assouline travel book – discover an excerpt from the guide and read about the secret stories behind the iconic destination.

Go with the Slow: The Rise of Train Travel

Belmond continues to shape the future of luxury train travel, marked this year by the arrival of the Britannic Explorer, the first train of its kind in England and Wales. Monisha Rajesh – author of four travel books including ‘Moonlight Express: Around the World by Night Train’ – discovers why slow travel is having a resurgence.

Quite the Site: Luxury Travel to UNESCO World Wonders

As proud custodians of historic properties near cultural and natural wonders, Belmond’s hotels and trains are the perfect choice for travellers with a historical hankering. Whether you’re marvelling at the ingenuity of the ancient Romans in Britain or the wonders of the Mayas in Mexico, our properties are your gateway to the past.